Indian higher education system has collapsed and quantity has replaced quality. While some parents and most students are aware of the state of affairs, the government is not concerned. The beginning of this systemic failure can be identified as the time private sector was given a free hand to enter this sector. I have written about the collapse of this sector here. So, will not dwell about the problem here but look at the solutions.

Acknowledging the problem

The education system at all levels — government, administration and even college levels, needs a wake-up call. The government needs to realize the seriousness and enormity of the problem and its repercussions on the future of the country. The government, at both central and state level, need to acknowledge the depth of this problem, that is the beginning of the solution. Most college administrators and even faculty know that they have been dishing out drivel to students. Acknowledging this would mean an existential crisis for them. They are unlikely to be the reason that the system will change. Students already acknowledge it as a problem but they have not tried to change the system. Instead, they have become part of caste-based reservation stirs, and this will only grow if the higher education system is not corrected immediately.

The demand for caste-based reservation agitations are gaining ground as the education system does not prepare students to be employed. This is a dangerous trend and it shows the dissatisfaction brewing in the aspirational class. The problem of higher education has been ignored for so long that it is accepted as one of the things Indians believe they have to live with. Prosperous parents look at foreign alternatives and do not see it worth their while to change the system.

There is no evaluation of the quality of education done at college level. At the school level, Pratham does a great job of evaluating standards. There is absolutely nothing at the undergraduate or post-graduate level. This is needed at this stage — maybe an organization like Central Square Foundation or even some of the founders of Ashoka University, ISB should look into this. Till we acknowledge and measure the state of current affairs, there is no way that we can move to the next step of improving or reforming it.

Systemic blindness

The higher education system comprises of both the undergraduate and post graduate courses, but for the purpose of this discussion we will look at the undergraduate courses. This is where the deeper malaise has crippled the system. From a systemic view there are four components — students, college or university administration, faculty and the government. All these four constituents of the system work and function in a vacuum of sorts. Students know the problem well, as they are the ones who face the job market, they are ones who are the most affected. Students are the ones most ignored in this system, primarily a didactic and geriatric system that looks down on them.

Unfortunately, students also do not realize or exercise their rights to demand a better quality of education. Student leaders are busy building a path to political careers and are little interested in education. Which is why student elections do not really serve the cause of students but are a mobilization exercise for political parties. As students have given up their right to reform or to improve the higher education system, it is left to the other three constituents to exercise them.

College and University administration has very little incentive to change the status quo. Higher education is also one of the areas where the private sector has failed miserably. All that is wrong with private sector comes out in its worst form in higher education. Private colleges have mushroomed exponentially over the last two decades, thanks to largese of politicians like Arjun Singh who opened the doors. As Minister of HRD, Arjun Singh allowed any moneybag to set up a college or even a University. This practice was followed at the state-level by even more corrupt politicians. As a result, a large number of private colleges are owned by political families.

The private ownership of higher education in the hands of politicians is a big reason that the government has not responded to this problem. The bigger danger is that the current political leadership will lose its relevance with its biggest voter base, the aspirational class, if it does not address this problem.

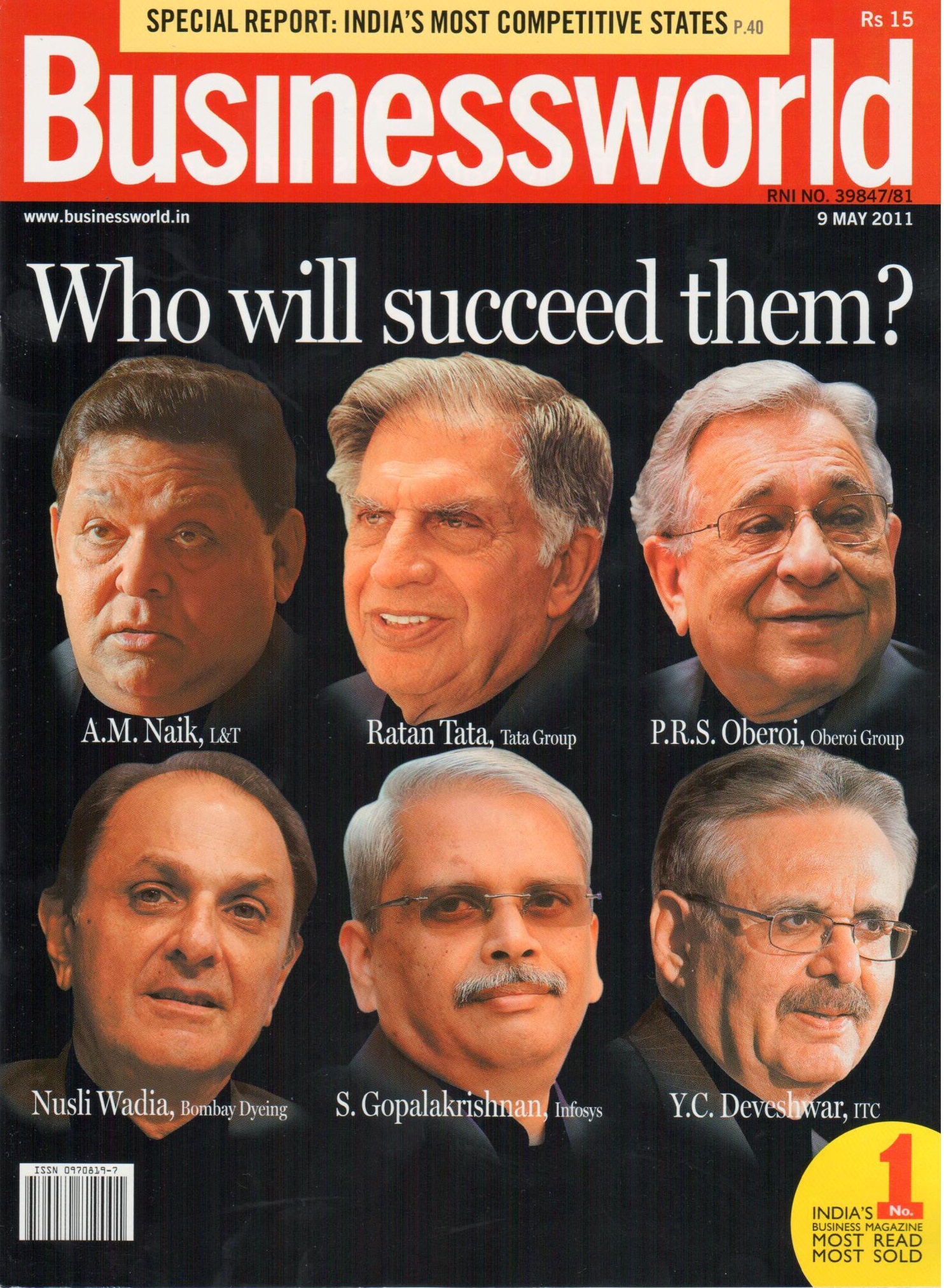

The government is the third and the most important constituent of the system, It regulates the sector poorly but is the only constituent that has the most to gain. Competitiveness is directly related and connected to the education system of a country as it is the reflection of the capability of its work force. Unfortunately, the government is obsessed with the IIMs, NMIMS, IITs and NITs of the country. Higher education to them always mean an IIT or IIM. These institutions are fine not because of any systemic efforts or even because of their own administration. They are good because they attract a brilliant set of students, the so-called crème de la crème. These are highly motivated students who do not depend upon the system for their learning. The industry has already recognized this aspect and does not hire them for learning but identifies these institutions on the basis of pre-selection.

The IITs or IIMs should not be taking the credit for the accomplishment or success of their students. An IIT taking credit for an IITian is akin to the tea shop outside AIIMS taking credit for the recovery of patients inside the hospital. Or the dhaba outside JNU taking credit for the political leaning of its students. Better still, the internet provider in IIT hostels taking credit for the computer science prowess of IITians. The government needs to act on higher education on a war footing if it any of its programs have to succeed in India.

Undue credit is given to IITs or IIMs as the government does not have anything else to showcase beyond these institutions. Faculty is the fourth and an important constituent of the higher education system. Here, poor quality is only matched by the huge demand. Good teachers want to work with public universities and colleges. There is prestige associated with working with an IIT and IIM that cannot be matched by any other. Though there is hardly any match for salary scales in some of the private colleges and universities — the pay is poor if not downright insulting, the workload punishing. Most private colleges are inadequately staffed with faculty handling multiple tasks, classes and even administrative responsibilities. Colleges do not want to pay anything to adjunct faculty as they seem as a fickle lot. While it is the adjunct faculty that is the solution to improving the quality of the faculty. But the biggest opposition to it will come from the existing faculty. This is where the gridlock starts and curbs any change of reform.

In a way the system acts against itself. The current world experience for students will not come from existing faculty but from the practitioners. Here the system calls it the industry interface, but it does not look at this interface as adding quality it looks at it as an placement exercise. Corporates also look at it as a marketing exercise. Chip design tool maker Cadence will tie-up with colleges to give its tool free. Cisco will train engineering students on its technology, IBM will do a server training exercise. The college become dependent on free faculty and training aids from these organization who are looking for conversion of students to its technology. As a result the college never builds its own capability or a capability of free agents who could plug into experiential gaps.

The job market has changed. There are more consultants and free agents now then any time before, long-term jobs are more a chimera than ever. In such an environment, how many public or private universities have created a process for attracting, compensating these free agents? There are several issues connected with higher education that need attention. Hopefully a bigger debate can start on this subject.

Published with First Post on October 17, 2016.