India’s Aspirational Districts Programme Focuses Governance Efforts On Development

By Amit Kapoor, Michael Green, Mark Esposito and Chirag Yadav

It is being increasingly recognised that economic metrics like the gross domestic product (GDP) do not provide an accurate picture of human development. As a result of its widespread usage, economic growth has become an end in itself rather than a means to better development outcomes. The Indian government has recently taken steps to shift its focus beyond the mere pursuit of economic outcomes to directly target the most deprived sections and regions of the country. It is doing so in the form of the Aspirational Districts Programme (ADP), which has taken up the task of focusing governance efforts on facilitating development efforts as a priority.

The programme was launched in January 2018 with an aim to improve the socio-economic status of the least developed regions across India. It maps development outcomes across five areas, namely health and nutrition, education, financial inclusion and skill development, agriculture and water resources, and basic infrastructure. Since the programme provides data transparency on the progress of the 112 districts mapped, it encourages the local administrations to ensure that developmental gains are realised on the ground.

The programme ecosystem allows different central and state government departments to work in tandem with each other along with the local administration, which were otherwise working in silos. It infuses the spirit of competitive federalism among regions to drive efforts towards common goals, and driven by competitiveness, districts strive to outperform their peers but also learn from them. It also encourages engagement with private partners on various facets of the programme from service delivery to data validation.

Apart from improving governance mechanisms at the local level, the programme was introduced with the idea to reduce regional disparities across the country. In India, the per capita income in the five most affluent states was 145 percent higher than that of the five poorest states in 2000, but in 2018-19, the gap was 400 percent (CMIE, 2020). Disparity exists within states as well, and the gap between the most developed and the least developed regions is only widening with time. The ADP endeavours to reduce that gap by improving the governance mechanisms in the least developed regions.

Even though the broader macroeconomic implications like regional equality might take longer to evidence productivity, the programme is already presenting rapid improvements in various social outcomes. For instance, as per data reported by the districts covered in the programme, the transition rate of children from primary to upper-primary level has gone up from under 88 percent to almost 95 percent on average within a span of two years. Similarly, the percentage of schools with functioning toilets for girls has increased from 87.6 percent to almost 98 percent on an average across the districts (NITI Aayog, 2020).

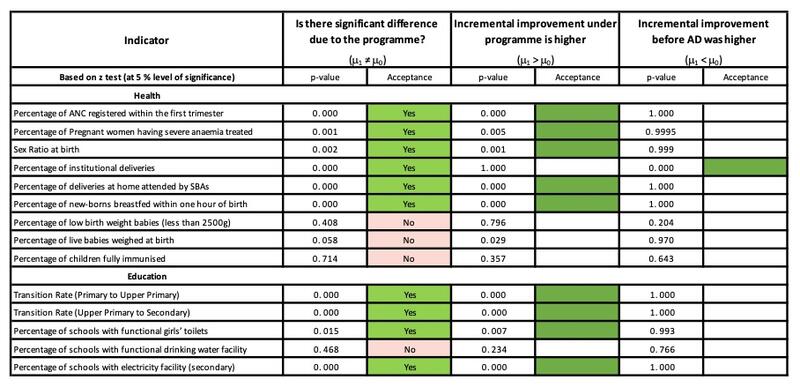

A recent study undertaken to assess the programme tested whether the impact due to the programme was significantly different from the status quo using a z-test (Kapoor & Green, 2020). It revealed that five out of nine health and nutrition indicators and four out of five education indicators registered statistically higher improvements under the Aspirational Districts Programme when compared to the progress that the regions were making on the same indicators prior to the start of the programme. These results are shown in Figure 1 in more detail. The first column of green boxes indicates that there was a significant difference after the programme began on the corresponding indicator. In case there was a significant impact, the other two columns indicate whether the impact was higher after the programme was implemented or before.

Figure 1. Impact of the Aspirational Districts programme on key development parameters

Best Practices

The study also noted several best practices that might facilitate replicating similar interventions around the world. First, awareness played a key role in the success of government efforts across these districts. For instance, the Shravasti district of Uttar Pradesh increased its immunization coverage from 31% in April 2017 to 72% in December 2018 through awareness activities about its benefits (NITI Aayog, 2020).

Second, data collection on a real-time basis across the key parameters of intervention has been central to the success of the programme. A dynamic dashboard monitors the impact of the programme and locates the nodes of improvement, which helps in identifying policies and interventions that are needed to drive change across the districts. The use of the data at the district level has allowed state and central administrations to be more responsive to local needs and allowed for a shift away from a one-size-fits-all approach.

Finally, a primary driver of the success of the programme, especially in a country as large as India, has been that it incentivised collaboration between different departments and tiers of the government along with private and civil society sectors. As the programme leverages assets and networks in a collective effort, it enhances the outreach capacity of the district administration in integrating the population.

As noted by Professors Michael E. Porter (HBS) and Scott Stern (MIT) about the Aspirational Districts Programme, “A striking finding is the impact of governance. Relative to a conventional top-down approach, the ADP supports active collaborations among multiple levels of governance within each ADP district, and the use of public-private partnerships. This stakeholder-oriented approach is driven by a shared understanding among the partners, and the use of a common language of outcome-oriented metrics and data.” By choosing such a collaborative approach, the programme is achieving success because it empowers the actors involved, ensures greater transparency and communication, and a better understanding of how the programme is being implemented on the ground.

The article was published with Harvard’s Social Impact Review on December 7, 2020.