The fable of the hare being defeated by the tortoise sounds familiar and is near universal. It is also the title of the recent book by T.N. Ninan, who uses it in the context of India to assess its long-term growth and competitiveness.

India has, at various points, has been referred to as a slumbering elephant, a roaring tiger and now by Ninan as the slow and steady tortoise. It is because it is seen as a country with an above average track record of growth since its ‘reforms by stealth’ began in the 1980s. It is also an economy that seems to be on the brink of transformational change.

Some of this has already started happening. The nation seems to be going through an interesting phase in its economic development. Recently the Rajya Sabha passed a bill on the Goods and Services tax, later approved by the Lok Sabha, which takes India closer to the dream of creating a common unified market.

Do not panic: this is not a column on the GST but on the more broader and substantial issues of India’s political economy. Ninan’s book and Vijay Joshi’s very recent one on India’s long road ahead seem to take a broad sweep of India’s political economy at present and its future course over the next few decades. These two books were proposed as a single book and ended up as two. We are glad that they did. It is because these assessments vary in scope and style and, therefore, so do the policy prescriptions in the two tomes.

Vijay Joshi’s “India’s Long Road Ahead”, is written more from an academic, theoretical and conceptual viewpoint. It tries to explain the role of the state and the market and how their performance fares in the case of India. The chapter on education and healthcare is particularly revealing and gives the case of ‘government failure’ and makes the case for better monitoring and careful analysis before increasing spending which has been the common wisdom in policy prescriptions for these sectors.

What is revealing is the author’s use of simple language to explain complex policy goals. The author describes the objective of India’s economic development as ‘rapid, inclusive, stable and sustainable growth of national income within a political framework of liberal democracy’. The simple objective shows clear and precise thinking on economic policy issues. The main arguments of the book can be described in terms of what it would take to become a prosperous country over the next few decades.

The main prescription is that the markets are thoroughly distorted and for the country to achieve the monumental task of rapid growth, it would need to unleash the creative energy of its workforce along with correcting the distortions of land, labour and capital markets.

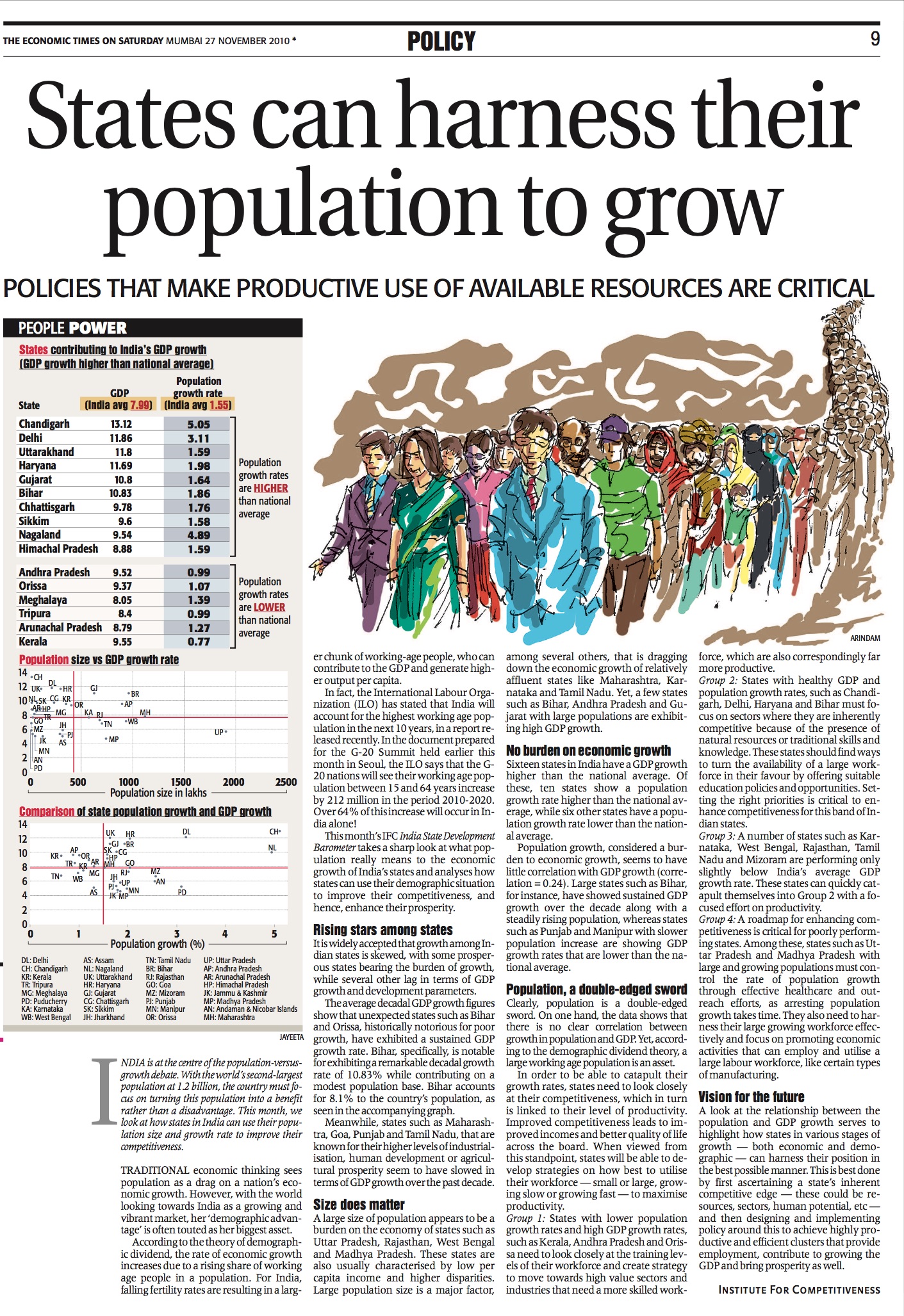

That will lead to productivity growth. Along with this, streamlining trade policy, entering the global value chains and an improved investment climate are cited as other areas requiring critical scrutiny. In spite of this India may not be able to achieve the ‘super fast growth’ defined as per capita income growth of 6 percent or above for three decades. It is because only three countries have achieved this so far — China (1977-2010, 8.1 percent) South Korea (1962-91, 6.9 percent) and Taiwan (1962-94, 6.8 percent).

Ninan’s book, “The Turn of the Tortoise” is written in a more journalistic style and in the manner of him being a more active chronicler of times. Ninan uses his pragmatic journalistic sense to try to frame a coherent framework about key issues and performance in key areas of national interest.

These include the manufacturing sector where India has underperformed, and continues to do so, due to the earlier license and quota raj. Also, described are individual stories of what works in India despite the odds — like the story of Baba Kalyani to get Bharat Forge to at least be in a position to manufacture guns for defense sector in India.

Similarly, Mangalyaan, Kumbh Mela and the 2014 parliamentary elections (the world’s largest) are seen to have worked due to them being pursued in mission mode. Ninan, like Joshi, contends that India has an underperforming state, which is also the case for failure of the government to provide basic services, and is rife with corruption. An example of public services being provided privately is in the case of healthcare sector, where 60 per cent of the hospital beds are now privately owned.

Ninan ends the book with three mega trends and a question on India’s liberal democracy. The three megatrends over the next 10 years to look out for are: First, change in the scale of markets. This is because India’s middle class will increase from 340 million in 2015 to 800 million by 2025. Second, shrinkage of state in sectors that are dominated by the public sector including banking and insurance, defence and even energy and mining. Third, shifting centers of gravity from New Delhi to state capitals and even at the third tier of governance at the level of urban agglomerations.

The book ends on a positive note by mentioning that the spirit of the present age is of greater freedom and the surface churn within the rumblings of a liberal democracy cannot hurt the country’s stability. In that sense, it truly is the turn of the tortoise. The two books overall offer rich insights for readers looking for understanding the present and future of India.

Published with Business Standard on August 9, 2016.