India@100: What’s ahead for urbanisation?

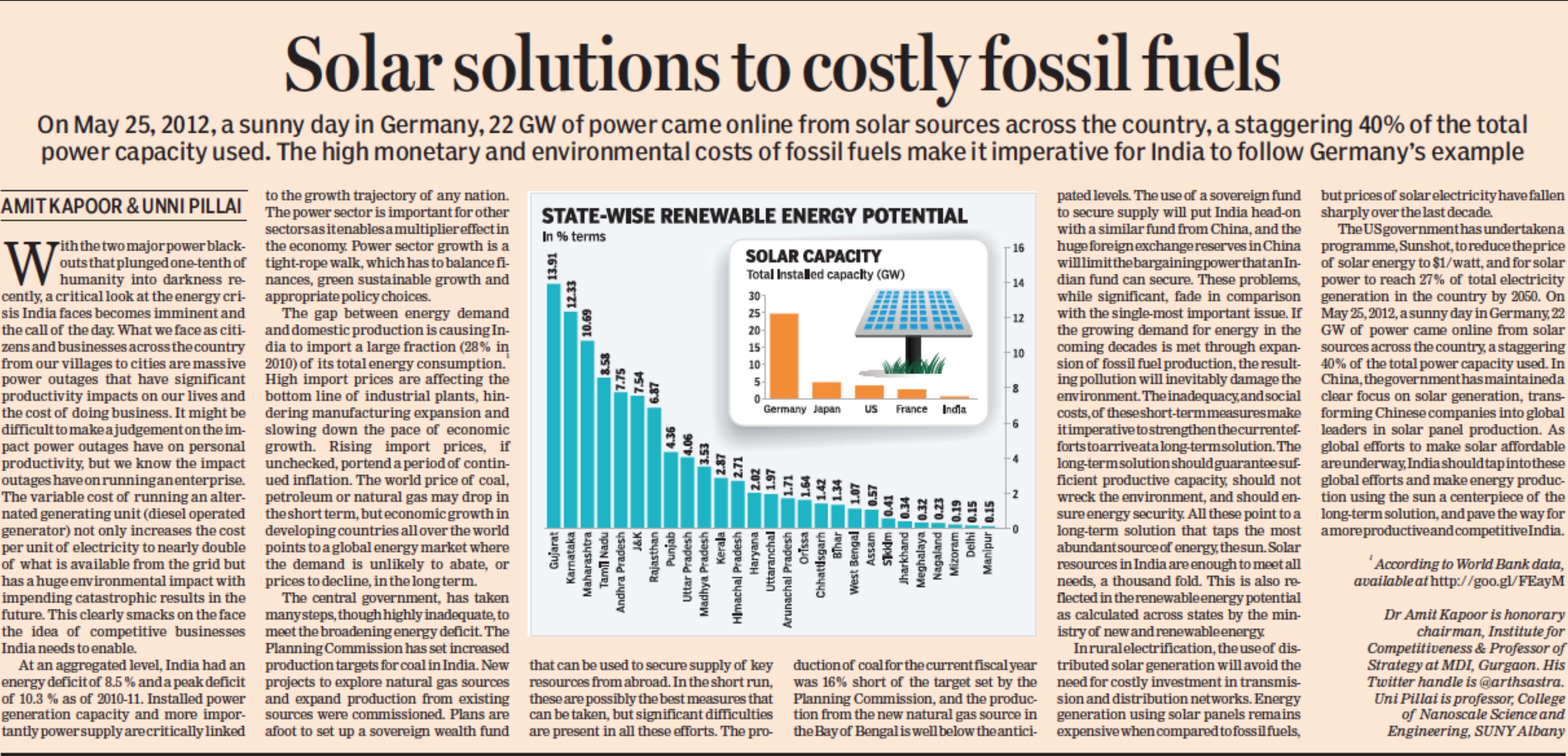

With India surpassing the United Kingdom to become the fifth-largest economy, the world is closely watching India as the country strides towards the next twenty-five years. One of the areas that will prove to be defining in India achieving its developmental goals is the pace at which it urbanises. Since the 1950s, the pace of urbanisation in India has witnessed a consistent rise. Even when the speed of this rise has not been similar to that of its peers, India has always prioritised planned urbanisation as part of its development strategy. As per the World Urbanisation Prospects (2018 Revision), a 2.4% growth rate of urbanisation was observed between 2010-2018. By 2022, India’s projected rate of urbanisation was expected to be 35.9%, and by 2047 this is expected to increase to approximately 50.9%. Despite having a pace of urbanisation lower than the BRICS nations, India’s focus on meeting the challenges in its development journey over the next twenty-five years has remained strong. India is well aware of the centrality of urbanisation in order to transform cities as engines of growth and is set on realising its goal of holistic progress. However, unwillingness is the least of concerns for India when it comes to increasing the pace of urbanisation. Rather, the nation’s cities are plagued with issues like sewage management, urban planning, declining water table and air quality that negatively influences the ease of living. In this context, we can identify two urgent issues facing India’s urbanisation journey – one, the issue of asymmetric patterns of urbanisation and two, the issue of planned urbanisation.

For the most part, urbanisation in India followed the trajectory of economic development. That is to say, cities developed in tandem with economic growth. However, this resulted in asymmetric patterns of urbanisation, with the states that saw economic growth, urbanised at a comparatively faster pace. For instance, a state like Kerela has a projected urban population of around 73.19% in 2022, which is expected to increase to over 96% by 2036. In comparison, states like Assam and Bihar have an abysmal projected population of 15.4% and 12.2%, respectively, in 2022, which is expected to marginally increase to 17.16% and 13.2% by 2036. Union Territories like Delhi and Chandigarh are projected to be 100% urbanised in the same time period.

One of the biggest challenges facing India’s urbanisation mission is in the face of asymmetric patterns of urbanisation. This slow and differentiated pace has often been characterised by India’s unique social structure and kinship ties that tend to restrict mobility. However, can India afford to continue with this narrative? As India has entered its ‘Amrit Kaal’ with a stern focus on achieving its developmental goals and transforming into a higher-income country in the years to come, it has to unequivocally target at matching the rate of urbanisation as prevalent among its peers. At the same time, India needs to pay attention to the impact of urbanisation on levels as micro as the districts as they shape up the larger economic spatiality of the country. In other words, urban districts roughly account for 30% of all districts in the country, with 45% of jobs and more than 55% of wages paid. These figures have been revealed in the Competitiveness Roadmap for India@100, which further posits that for a well-spread and shared growth, India needs to focus on the districts lagging behind and push for a faster rate of planned urbanisation. In addition, the limited level of internal migration adds to the concern of inadequate distribution of resources along with the lopsided pace of urbanisation. There are no restrictions on internal movement in the country. However, the last Census data (2011) shows us that the bulk of this movement has concentrated or followed the same pattern of migrating to specific states or from one district to another.

At the same time, the issue of planned urbanisation has exposed the country to another host of troubles that it needs to look at. With an expected urban population of close to 630 million by 2030, the emphasis should not only be on urbanisation but on planned urbanisation. By planned urbanisation, it is implied that equal emphasis is placed on aspects of city design, planning and governance. Well-planned cities lead to value creation through optimal distribution and utilisation of resources. Additionally, it fosters ease of living and prosperity through sustainable growth and economic productivity that the residents can benefit from. In many ways, even the difficulties that urbanisation brings offer excellent chances to redesign cities by looking at sustainable objectives and socio-economic growth, which will only result in a more stable social structure. To this extent, India needs to target key reform areas, from remodelling its urban governance system to making it more people-centric.

As India rises globally, it is expected that the country will be widely watched and will be a rising power in its own right. Nonetheless, there is a need to speed up urbanisation in the nation. The urbanisation rate must be regulated to prevent the population surge from being limited to larger cities. It is also essential to closely monitor the rate of urbanisation as it will aid in the process of building sustainable pathways to socio-economic development in the country. A dual focus on planned and uniform urbanisation will go a long way in attaining global recognition for India’s urban story. If targeted and continued efforts are made now, the next two decades can be pivotal in achieving these projections by 2047 and achieving a higher rate of social progress.

The article was published with Business Standard on September 21, 2022.