This pandemic could act as a starting point for the re-orientation of the primary and district health care systems of Indian states to keep the infections at a manageable level. As India looks to flatten its curve, its state governments need to remember that it cannot move ahead by leaving the Covid-19 vulnerable population behind.

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended people’s lives, leading to a massive death toll across the globe. Similar to other countries, India has also not been able to sidestep the wrath of the virus, with total deaths going beyond 1500 and confirmed cases, crossing the 46000 mark. In order to combat the spread of infection, the Indian government has taken stringent but necessary policy measures of imposing a national lockdown since 25 May 2020. With economic activity coming to a grinding halt, people have been trying to stay at home to ride out the adverse effects of COVID-19.

While the virus has indiscriminately been deadly for all, certain sections have been more vulnerable to the disease than others. Within the broader ambit of infected and instances of death, it has been noticed that vulnerabilities differ according to age cohorts and co-morbidities. According to data from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, more than half of total COVID-19 deaths in India are among those aged above 60 years of age. People with co-morbidities like diabetes, heart disorders, kidney ailments and other diseases have accounted for 78 percent of total deaths in India. This is because the elderly, in general, have significantly decreased immunity and body reserves, which is exacerbated if there are any underlying health issues. With India’s 1.3 billion diverse population representing a multitude of health, economic and social disparities, the added vulnerability factor of COVID-19 presents a unique challenge.

As India moves towards lifting its lockdown and resuming normal operations, it is this vulnerable population that needs protection. Nonetheless, it is easier said than done – understanding the existence and condition of the defined vulnerable group across states would be the first step to creating effective post-lockdown strategies. Additionally, the added intersectionalities of economic and social poverty attached to the elderly and chronically ill population would make it hard for states to have a uniform path to addressing the needs of the vulnerable population. With the future of COVID-19 vaccine still not being an absolute guarantee, government agencies and civil society would have to come together to help quarantine the elderly and those with co-morbidities, in order to limit further COVID-19 deaths and ease the burden on existing health infrastructure.

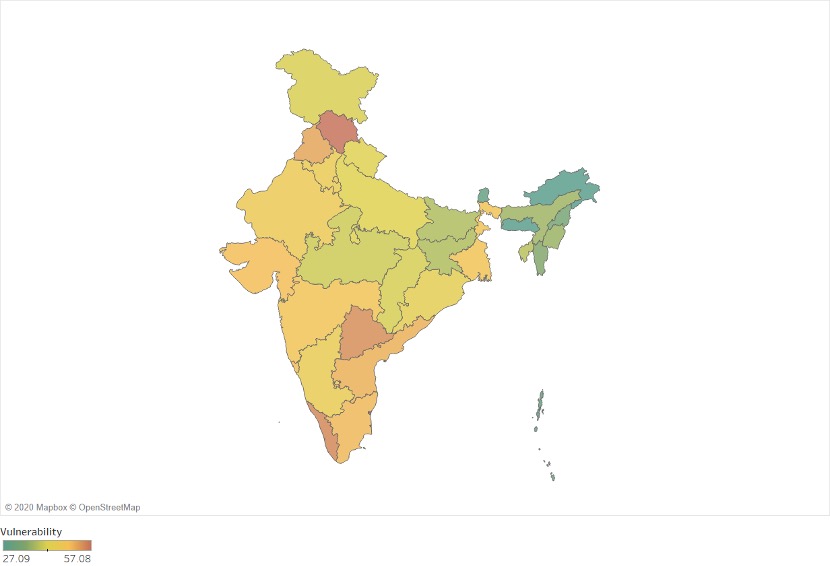

As an initial step of envisioning post-lockdown steps, the Institute for Competitiveness has developed a COVID-19 vulnerability index for Indian states, by mapping indicators related to health infrastructure, population demographics and underlying health issues. While the index is meant to act as an analytical tool for Indian states to judge their magnitude of COVID-19 vulnerability, it is not indicative of the current actions of the state governments.

The COVID-19 vulnerability index highlights that across all the 36 Indian states and Union Territories, highlight that Himachal Pradesh is the most vulnerable state while Meghalaya is the least susceptible state. When the Indian states are broken up into cohorts of – large and small states (in terms of population), hill states and Union Territories – Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Himachal Pradesh and Puducherry emerge as the most vulnerable, respectively.

Checking for the specific pillars, the Health infrastructure vulnerability pillar reveals that Jharkhand is the most vulnerable in terms of its health infrastructure capacity. While Jharkhand has inadequate coverage in terms of households covered by health scheme/insurance, low government beds and Community Health Centres per lakh population and high vacancy of doctors at district hospitals, its vulnerability in population demographics and underlying health issues have been relatively lesser than other Indian states and union territories. Nonetheless, with a sudden increase of migrant influx from other states, Jharkhand could face problems in dealing with rising COVID-19 cases.

However, it is especially alarming that while Maharashtra is the leading Indian state in terms of COVID-19 confirmed cases, it is alsothe second most vulnerable in terms of health infrastructure vulnerability. The state also has a high percentage of the elderly population, in relation to other states, highlighting further scope of increased COVID-19 cases.

In terms of population demographics, (including density and age-related population) Kerala is the most vulnerable, followed by Telangana. Kerala has the highest population of the elderly in India and a relatively high population density. Nonetheless, its low vulnerability in the health infrastructure pillar and definitive measures taken by the state government to “reverse-quarantine” the elderly and chronically ill population has led to the flattening of its COVID-19 curve. Telangana, on the other hand, though having a relatively low population density, has a significant section of the elderly population, with India’s highest percentage of 70-79 aged population residing in the state. While it has a comparatively lesser population diagnosed with co-morbidities, it is ranked 9th most vulnerable in terms of health infrastructure availability. This implies that the state might face issues if there is a sudden increase in COVID-19 cases among the elderly.

With respect to underlying health issues, Himachal Pradesh is the most vulnerable state, having the highest percentage of hypertension and diabetes diagnosed population. Moreover, it is the 3rd most vulnerable in the population demographics pillar as well, having a high percentage of the elderly population. Nonetheless, it is among one of the least vulnerable states in terms of health infrastructure capability, the implication of which is also highlighted in its high COVID-19 recovery rate (92.68%). The state has also taken up stringent measures to counter the rise of cases by – screening their entire population for influenza-like illness, increasing testing capacity, ensuring an adequate supply of PPE for health professionals and segregating existing health care systems based on the degree of the COVID-19 infection.

As COVID-19 becomes a “new normal”, Indian states can no longer overlook the different needs of the elderly and immunosuppressed population, especially in the times of the pandemic. With central guidelines having specified the need for “persons above 65 years of age, persons with co-morbidities, pregnant women and children below the age of 10 years” to stay at home, it remains to the Indian states to effectively implement the same. One of the ways that the elderly and chronically ill could be incentivised to continue with their quarantine would be delivering medical and non-medical essentials right to their doorstep so that they do not have to step out. Volunteers could also physically check up on the elderly and those diagnosed with co-morbidities at least once a week while carrying out social distancing. This is especially important for the elderly and chronically ill who are staying alone and do not have any social networks to fall back on.

In the long term, with better data monitoring, officials could frequently check up on the health status of the vulnerable population and take necessary steps based on the real-time information. There could be a better chance of recovery in terms of COVID-19 confirmed cases if there is early detection of the infections. Primary health care officials could be trained to provide care to the elderly and chronically ill at home, to reduce the burden on health infrastructure at designated COVID-19 hospitals.

This pandemic could act as a starting point for the re-orientation of the primary and district health care systems of Indian states to keep the infections at a manageable level. As India looks to flatten its curve, its state governments need to remember that it cannot move ahead by leaving the COVID-19 vulnerable population behind.

The article was published with Economic Times on May 7, 2020.