Demographic danger: India’s population is not just exploding, it’s happening in a way that threatens the nation’s productivity

As countries develop and the general populace becomes more literate and affluent, the birth and death rates witness an unambiguous drop. There are many factors that drive these trends, but a resultant outcome for every developing nation is the so-called ‘demographic dividend,’ where the population in working age rises faster that those outside it, who are usually dependent on the former for survival.

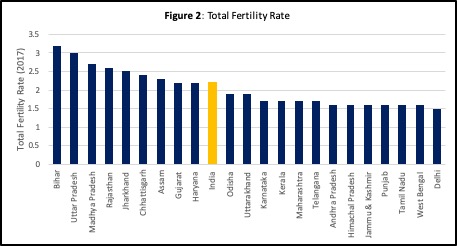

India’s fertility rate, or the number of children born to each woman, has halved since 1980. The average fertility of the country between 2015 and 2020 stands at 2.3 per woman against an average of 4.97 recorded between 1975 and 1980. The current fertility rate is very close to the replacement level of 2.1 percent, which is the number of children needed to replace their parents. A fertility rate below the replacement level will imply a fall in the country’s population.

As a result of the fall in fertility rates, more people are entering the working age than are being born. The level of dependency is falling, and the country has entered a phase of demographic dividend, which could give a boost to the economy via higher levels of income, savings, and productivity. Leveraging this transition period efficiently by exploiting the full potential of the human capital will lead to rapid economic growth.

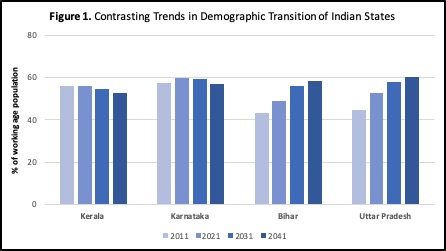

But since India is such a vast country with contrasting trends across the land, different states can be found at different levels of demographic transition. This has been depicted in Figure 1. The graph shows that the share of the working population will be declining for most of the states in the southern region. Kerala’s working age population will experience a sharp fall from 56.2 percent in 2021 to 52.8 percent in 2041, while Tamil Nadu’s work force size would shrink by 2.8 percent during the two decades starting from 2021. On the other hand, due to the high fertility rates in the central and the northern region, the growth potential for the country is largely locked in states like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh. In 2041, only four states – Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Uttar Pradesh will contribute to 43 percent of the country’s working age population. In Bihar, the share of the elderly will be as low as 11.6 percent by 2041.

The difference in the levels of demographic dividend can be explained through the total fertility rate (TFR). Thirteen out of twenty-two major states now record fertility rate below the replacement rate of 2.1 as can be seen in Figure 2. The rest of the states that have a higher TFR than the replacement rate, which implies that their population will keep on rising over the next few decades allowing for a rise in the working population and, thus, the demographic dividend.

These regional differences in the age structure have significant policy implications for the states. A mere presence of the labour cannot assure high levels of growth and development. To exploit the time specific window of opportunity, northern states should focus on policies that will enhance the productivity of their workforce and will bring more job opportunities. This implies a larger focus on the provision of health infrastructure with a greater emphasis on child health, programs to address issues such as child marriages, and policies to improve the quality of education system and ensure gender parity in education.

On the other hand, the states where the window of opportunity is closing soon should focus on empowering women to increase labour force participation rate so that they can further encash on the demographic dividend. These states will also require workers that will lead to increased migration from other states, which would bring with themselves a host of other challenges. Moreover, to support the elderly, policymakers in these states should also focus on improving their pension systems.

In a nutshell, the regional diversity in the age structure requires Indian states to work on different policy lines by factoring in population dynamics to reap the socio-economic benefits.

The article was published with First Post on August 16, 2019.