Several economies have been built on the manufacturing sector. Many economies are driven solely on the basis of their manufacturing capacities, and it’s a fact that has not been hidden from India. In this context, India has been considering strategies to increase manufacturing for a very long time, and there have been earnest and effective attempts to do the same in recent years. The Make in India initiative, Production Linked Incentive Schemes for 14 key sectors, National Logistics Policy and the Industrial Corridor Development Programme, are some of the Indian policy efforts in line with ramping up manufacturing in the country. These policy initiatives reflect the importance India has attached to its manufacturing sector. However, the point that growth in the service sector has outlasted that of manufacturing – unlike several other countries – has led to a more active and rigorous push in the sector. It has been a popular belief that the manufacturing sector has enormous potential to create jobs and absorb surplus labour that would otherwise be used in agriculture. Its potential has also been attributed to its capacity to take on unskilled labour for labour-intensive jobs. India has strongly emphasised on its industrial sector to generate an increasing number of jobs. The country has been striving hard for a long time to get its industrial industry to add to a rising pool of jobs. But it is crucial to supplement these initiatives with a focus on creating market-competitive jobs.

The key to enabling long-term economic growth is to put more emphasis on enhancing workers’ productivity and skill sets. In this context, creating more ‘competitive jobs’ should be the prime focus. Competitive Jobs can be defined as “jobs that provide pathways to higher productivity and enable individuals to earn their own livelihoods and become self-reliant”. In other words, competitive jobs encourage workers to earn their living in the market, support their way of life, and offer chances for long-term skill and productivity growth. These jobs foster an environment where an individual’s output, capability, and value addition can increase. Simply put, a competitive job allows employees to diversify their skill set and increase their value. In this respect, competitive jobs do not let an individual’s capacity to languish.

Paul Krugman once wrote, “the capacity of a country to improve its standard of living through time depends almost entirely on its capacity to increase output per worker”. In India, informal employment makes up a sizable portion of the labour force. In fact, the ability to develop human capital and enhance performance over time is limited by informality and irregularity in employment. With few incentives to invest in the resources that would increase production, it stifles worker capability. Productivity is seen as “essential to addressing today’s many challenges” in the ILO’s Global Employment and Social Outlook 2023 study, and India has the unrivalled ability to lead the increase in global productivity.

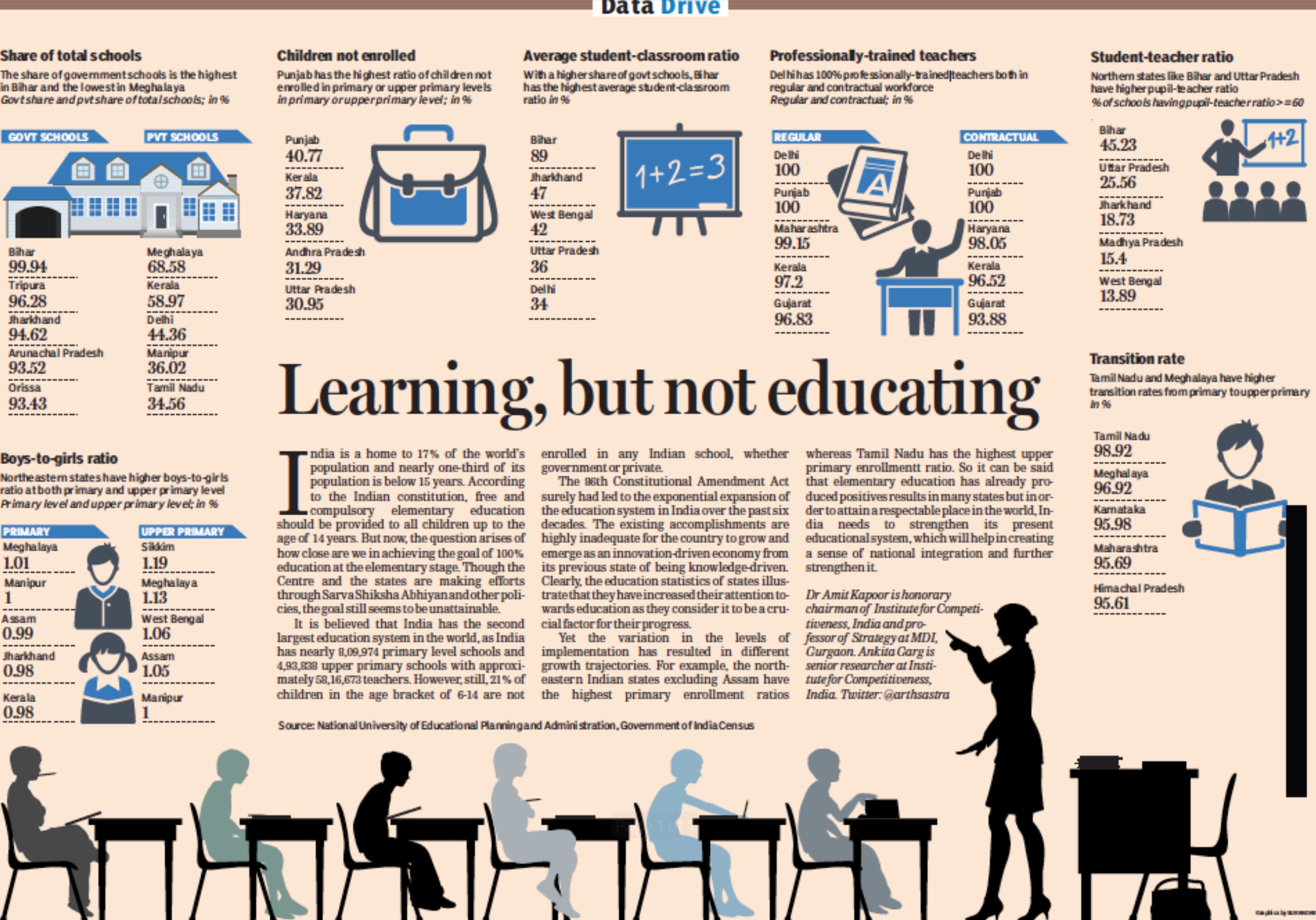

In India, there were 900 million working-age individuals in 2020, and by 2030, that number will increase by more than 100 million. India’s working-age population is predicted to surpass China’s working-age population in the near future, all due to a growth rate of about 10 million people every year. The debate about the benefits of effectively utilising our demographic dividend is gathering traction. On the other hand, a wave of the digital revolution has slowly made its way across the country, changing lifestyles and means of subsistence. Together, the two aforementioned developments could lay the groundwork for a more prosperous India. The fact that there were 117.8 crore telephone subscribers in India as of 2022, with 44.3% of those subscribers living in rural areas, illustrates the pervasiveness of digitisation. On the Unified Payment Interface, almost 8 billion transactions totalling nearly $200 billion, were made in January 2023. Digitisation and a growing youth population can be combined to develop more competitive occupations. India can concentrate on two areas as the landscape of work changes due to the changing nature of work. One involves investing in human capital that has not yet entered the workforce, and the other involves making productivity enhancement a continual process for those already employed. A skilled workforce is only one aspect of the equation. The demand for faster GDP development is also a requirement for India’s competitive job creation. According to McKinsey’s research from 2020, net employment would need to increase by 1.5 per cent annually from 2023 to 2030, while productivity growth was kept at 6.5 to 7.0 per cent annually in order to meet the expanding employment needs.

To plan our path towards India’s centennial year, substantial efforts are being made. Amrit Kaal will become a reality not only through one specific pathway but through a number of channels that work in concert to increase the positive effect. The creation of competitive jobs must be prioritised in addition to placing a stronger emphasis on expanding manufacturing. India will ultimately benefit from letting go of the idea that employment in the manufacturing and service sectors are mutually exclusive and putting more effort into creating competitive jobs across all industries.

The article was published with Business World on May 30, 2023.