We will come out of this catastrophe with not only positive changes, but negative practices as well.

The Covid-19 pandemic affects every aspect of human life from our health to the economic system. While the human race has known widespread famine, war, and plague in the past, the sum of changes occasioned by COVID-19 is unprecedented, because the impact has almost simultaneously reached all regions of the world. On the economic front, COVID-19 has acted as an accelerant of major trends already in progress. Policymakers can only make assumptions about the different paths our future could take based on the economic theories at their disposal. Mainstream economic theories, however, have assumed globalization as a natural continuation of economies of scale. They have not dealt sufficiently with both the positive and negative aspects of the global value chain in a tightly interconnected world.

The present condition is entirely different than what was seen in the past because of the globalized nature of the economy. National economies are more interlinked to other nation’s economies than ever before. While impact on one nation’s economy can have resounding impact on other nations, the impact of pandemic on each nation individually has had a manifold impact on the global economy at large.

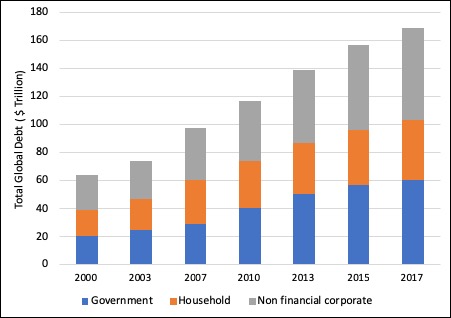

Therefore, no past financial crises are adequate guides to predict the post-pandemic economy today. Nevertheless, financial crises in the past did signal a fundamental change in economic thinking. The post-World War 2 economic thinking was largely inspired by Maynard Keynes’ general theory. Post-pandemic economic thinking needs to undergo a similar fundamental change.

A direct hit at the global economy has been the disruption of the global value chain (GVC) by the pandemic. From research and development to the final product, the stages of production are dispersed across the world. In other words, economic motivations have led to both worldwide economies of scale and to disaggregation of national value chains into specialized roles in a global value chain – if China is the manufacturing hub, sub-Saharan African countries are suppliers of resource-based goods like oil and minerals. The model has proved to be efficient and especially beneficial to the developing countries, but it has also proved to be a fragile model during this crisis. For a start, the city of Wuhan, from where the outbreak began, accounts for a significant global market share in the production of optical fiber cable and related devices. The effect of the shutdown of production in the city reverberated in the international value chain even before the disease reached other parts of the world.

While the US-China trade war had already begun to cause disruptions in the GVC, the Covid-19 pandemic expedited the phenomenon. The pandemic may not bring an end to GVC or globalisation per se, but it nevertheless will provoke a rethinking of the modelling of the value chain with greater focus on building resilience. One expects participants in the value chain to hedge risk by distributing upstream suppliers and downstream distributors across multiple regions. Meanwhile, the national economies will also have to rethink alternatives to reduce their reliance on the GVC, which may result in some reshoring and diversification of value chain.

On a related note, the pandemic has made us realize that markets also cannot work with the single motive of profit maximization at the of human life. The crisis has highlighted the inter-dependence between market and community. The corporates rely on communities for their operation, and the pandemic affecting the society has consequently affected business operations. While it has long been argued that markets cannot have a free reign in the long run if they ignore the communities, the pandemic has driven home the point. It calls for rethinking of the role of the markets.

The idea of corporate governance and social responsibility had been floating around in the corporate world for quite some time, but the pandemic may force businesses to take greater cognizance of the same as requirements for participation in global business. Climate change is another phenomenon that has lately induced businesses to restructure their business practices to be more environmentally conscious. As greater sections of the society put a value on environmental sustainability, their consumption patterns would also reflect that. So, with the positive effects of lockdown on the environment becoming apparent, there is gradual mounting pressure on businesses to account for ecological concerns in their operations. If the environmental challenges inspired businesses to market an ecologically conscious brand image, the pandemic might force them and more to look beyond profit maximisation and towards social responsibility in order to compete in the market. This shift in focus might change the fundamental basis of competition and by extension the model of growth in the near future.

The role of government has also undergone a monumental change in this crisis. Governments around the world have spread themselves thin by increasing healthcare expenses as well as pumping fiscal stimulus into the economy. However, fiscal spending has its limitations, especially at a time when revenues are not being generated. It reinforces the point that corporates would ultimately have to assume greater roles in delivering on their social responsibility goals and help sustain their business ecosystems.

However, an offshoot of the pandemic has also been the rise of authoritarianism. Between capitalist states and socialist states, every country on the continuum has been found ill-prepared for a crisis of this magnitude. Nevertheless, the response to the pandemic has been more effective in countries like Singapore, Hong Kong and South Korea that adopted rigorous testing as well as strict measures. Some measures like close surveillance and monitoring of citizens even raised questions about privacy but the opposing argument was that such interventions are justified if it helps control the spread of the disease. Some governments like Hungary and Hong Kong have even taken this pandemic as an opportunity to centralise greater powers in their hands. Now, even after the pandemic is curbed, such governments may continue to exercise unchecked power.

Another difference that separates Covid-19 from other past financial crises is the existence of internet. it is the first pandemic in the age of internet. At a time of economic lockdown in most parts of the world, The internet has been the saving grace in ensuring a steady flow of information as well as making remote-work possible. It has been beneficial for governments and policymakers to anticipate risks, compare solutions and to coordinate efforts. Further, by pushing us to take some of the operations over to the internet, it has opened fresh debates about the future of work, business, education, and the like. The prolonged lockdown has made people accustomed to online learning and remote work and got the experts contemplating about the merits of continuing such a practice, given its cost efficiency.

Overall, the pandemic has made us rethink economic institutions and mankind’s approach towards the environment. Hence, it has also propelled a reimagination of the role of the market and the state. The society may come out of this catastrophe with some positive changes, but it may also set in motion some negative practices. The task for nations would be to navigate these opportunities and challenges. All in all, this may herald the beginning of a new economic order.

The article was published with Economic Times on April 26, 2020.